Uluru – Icon of Australia

At the end of May 2017, Uluru stood as a silent sentinel over an historic summit of the First Nations of Australia. They had come from across the continent and the Torres Strait Islands, 250 community leaders. At the end of 3 days of deliberation, they issued a powerful and beautifully crafted document, entitled Statement From The Heart. It rejected symbolic recognition. Speaking from the “ torment of powerlessness” it demanded a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice in government decision-making. It also called for a Makarrata Commission to supervise agreements with government and lead the way to a treaty.

WomanGoingPlaces affirms its supports for the Uluru Statement.

This summit and the charter it produced added another dimension to the political, cultural and spiritual significance of Uluru.

Uluru is one of the few places in the world to have been awarded dual World Heritage recognition – for both its outstanding natural values and outstanding cultural values.

On our trip to the Red Centre of Australia, we found extraordinary beauty, cultural richness, and new perspectives on this iconic Australian landmark.

We began with the perspective on Uluru from the distance, at both sunrise and sunset. In the darkness of early morning, we watched as a dark shape outlined by the first rays of the sun began to loom over the flat plain. By day, we saw a monolith, 9.4k in circumference, rising up 348 metres from the semi-arid desert that surrounds it. Both the rock and the sand are stained a deep red by the iron oxide in the earth. Late afternoon, we watched from afar as the sunset coated Uluru pink, then rich purple colours.

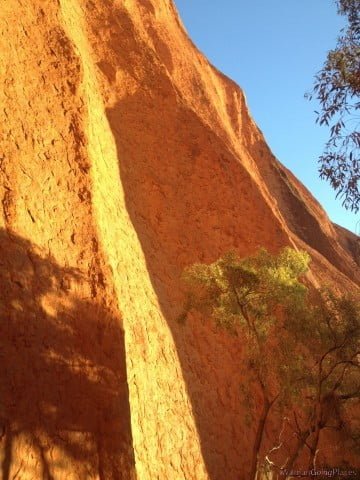

But nothing really prepared us for the shock of seeing Uluru up close.

It is not a uniform lump of rock. As you walk into it, you discover oases with vegetation, waterholes, waterfalls, caves with rock art, gullies and rocks sculptured into remarkable shapes. Changes of light, shadow and perspective bring with them continuous shifts in appearance, an impression of movement at odds with the idea of a stolid monolith.

In the tranquility of the Kantju Gorge, we were enclosed by towering rocks that spectacularly changed from yellow to gold, orange to ochre, pink to purple, and brown to grey.

This breathtaking physical perspective is only a part of Uluru. We began to see that there is another more compelling perspective. We began to learn about the Anangu, the Aboriginal people who are the traditional custodians of Uluru and the country around it, and we pay our respects to them. Their traditional languages are Pitjantjatjara and Yankunitjatjara. Carbon dating on caves, shows that indigenous people have lived in this area for at least 22,000 years, and possibly 30,000. Elsewhere in Australia, there is evidence of Aboriginal habitation dating back to around 60,000 years, making them one of the oldest human societies on earth.

Traditional custodianship is quite different from our concept of land ownership. It is not personal possession, but public, common responsibility to care for the land, its flora and fauna, and to carry on that care from generation to generation.

For thousands of years, the indigenous people have passed down the knowledge of how to survive on the land and how to survive as a community. But they have not written it down. There are no written texts. There is no sacred literature. They have no Bible, Koran, Sutras, Vedas or Chinese Classics that have guided the survival of other peoples.

It is an oral tradition that has sustained the Aboriginal people with a strong culture in Australia for 60,000 years, in some of the harshest terrain on earth.

The landscape is their sacred text. The land is endowed with sanctity. Aboriginal spiritual heritage, history, laws, culture, knowledge, geography are all embodied in the land. They read their land – its shape, its contours, its plants, animals and birds. And they express this connection to the land through songs, stories, ceremonies and art.

The foundation of the culture is called Tjukurpa – Creation – when the ancestors, changing shapes between humans, animals, birds and spirits, roamed the formless land. Their travels, battles and experiences gave shape to the land and created its distinctive topography and all life. As well as creation stories, Tjukurpa is a body of knowledge governing human behaviour and care of country.

According to Tjukurpa, Uluru was formed by Two Boys. They were playing at the Kantju waterhole, piling up mud until it was the size of Uluru. The long channels and gullies on the southern side of Uluru were formed when the Two Boys slid down from the top on their bellies, dragging their fingers through the mud.

The python woman, Kuniya and the poisonous snake man, Liru, are other ancestors who shaped Uluru and left visible marks. Signs in the rock chronicle their struggle and the places where the grieving Kuniya struck Liru dead in vengeance for spearing her nephew.

When visiting Uluru, you are not just walking amongst boulders and rocks. You are following the path of the creation stories that the Anangu continue to celebrate. The spirits of the ancestors are believed to still dwell here so it is considered sacred, and parts of Uluru are closed to the public.

The initiation of the young into the complexities of Tjukurpa continues. And in caves in Uluru, grandfathers pass down knowledge to young boys, drawing on the cave walls as a teacher in any other classroom would illustrate on a blackboard. In separate caves, women elders pass on women’s business to young girls.

It is an ancient culture that is still alive and still defines the indigenous people.

Another new perspective we had on Uluru was looking up to the desert sky – the stark blue of the sky by day and the sheer brilliance of the night sky. Since tourist and local accommodation is concentrated in a particular area, the township of Yulara, electric lighting does not blot out the stars as it does in cities. You can look up and clearly see endless swathes of stars shining directly above you.

Uluru is within the Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park which covers 327,414 acres of Australia’s desert outback. In 1985 title deeds to the land were handed back to the Anangu, and it is managed jointly by the traditional owners and Parks Australia.

The Cultural Centre in the National Park is very beautiful. Built from mud bricks, it represents the two ancestral snakes, Kuniya and Liru. Inside, there are outstanding exhibits about Anangu culture, and you can purchase original indigenous artworks. The bookshop also provides information on a variety of walks around Uluru. Different tour companies also offer tours.

Since Uluru is a sacred site, climbing the rock is disrespectful. It is also dangerous, so visitors are requested not to do so.

The best times to go are during the Australian winter and spring, when the nights may be freezing, but the days are mild. In summer, temperatures can be extremely hot with outdoor activity limited to the morning hours.

The hotels all belong to one group so there is not much competition, but there is a range of accommodation from camping to 5-star tents and hotels.

Our photos were taken only where permissible. To see each photo separately go to our Gallery page.

Photography – Rosalie Zycher & Augustine Zycher

Video editor – Augustine Zycher

Music – Albare CD ‘The Road Ahead’ title track www.albare.info

If you liked our post, please consider becoming a supporter of

A social enterprise advocating for economic security and social inclusion of Australian women aged 50+.

We campaign against the discrimination and general invisibility women 50+ face.

We tell the stories of women 50+ who are re-defining how women age.

SUBSCRIBE to receive latest posts in your Inbox.

SUPPORT our advocacy and keep us accessible to all women.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!