999 Names for an Old Woman

Google offers over 999 words to describe an old woman, and they are uniformly pejorative. The top 4 are: “ distressingly ancient; squat and dumpy; dismal and lonesome; insanely suicidal.”

Some common names for old women are: old bag, granny, biddy, crone, hag, witch, harridan, bedlam, old bat, old boiler. And if that’s not bad enough, you can also resort to descriptions such as: “withered and bitter; almost well-dressed; unnaturally lusty; crazy and uncanny; entirely uninteresting; exceptionally invaluable.” Then of course there is the word ‘ boomer’ which has become a synonym for greed, undeserving wealth and selfishness.

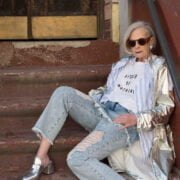

In a society that values women primarily for their youthful beauty, sexual and reproductive powers, the more we age, the more our currency as women is devalued.

This devaluation is reflected in the language. The appellations for older women denote worthlessness, weakness, ugliness, helplessness and even evil. It’s also not clear at what age you become classified as an old woman.

“Throughout many periods of history in the West there has been a real worry about what you do with women who are past their childbearing years,” says Mary Beard, Professor of Classics, Cambridge University.

What’s in a name, you may ask. The answer is – a minefield. Language reflects and reinforces prejudice and discrimination and has terrible consequences. Arguably, there is a direct link between this gendered ageism and the social crisis that Australian older women are now experiencing. It is a multi-faceted crisis that is distinctive to this demographic. It negatively affects their employment, housing, livelihood, and mental and physical health.

Older women are ending up on the dust heap of the nation’s economy. Women aged over 50 constitute the majority of unemployed and those on Jobseeker. These are women who for the most part are educated, have skills, professions and careers, and have spent decades in the workforce. And yet, the widespread ageism of employers, documented by the AHRC, now bars them from the workforce.

Nevertheless, the Government continues to impose ‘mutual obligations’ where older women are forced to keep up the debilitating charade of applying for jobs that they have no hope of getting, precisely because of gendered ageism.

Government attitudes and practices also contribute significantly to making older women the fastest growing demographic becoming homeless.The latest report on homelessness recognises that ”older low-income earners, particularly those on fixed government benefits, experience more homelessness.” It reports that at least 270,000 people aged 55+ are already homeless or at risk of homelessness, most of them older women.

In the budget earlier this year, Treasurer Jim Chalmers came the closest he has to acknowledging that older women face the barrier of discrimination. However, all he did was to increase their Jobseeker payment by only a few dollars a day, still keeping them well below the poverty line. The Treasurer and the Labour Government have yet to recognise that there is a distinctive crisis affecting tens of thousands of women in this demographic. They must recognise its scale and importance. And they must recognise that at its core lies the systemic gendered ageism that is so pervasive in both government and society. Otherwise they will never actually address the crisis as a comprehensive package.

And this crisis is set to rapidly escalate. By 2030, one in three Australians will be over 55. The number of Australians over 65 will double in the next 40 years. The majority will be old women.